Residency Report by Tom Lee

IN the LAB Residency with Koryu Nishikawa V & Hachioji Kuruma Ningyo. August 19-27, 2015

SPONSORED BY TCG / Andrew W. Mellon Foundation

I first met Koryu Nishikawa V, the remarkable Japanese traditional puppet master who has become my mentor and friend, ten years ago. Returning to Japan this August through the In the LAB Program, it is hard to believe how much time has passed since that first encounter. In many ways, I still feel like a student with Koryu-san: astonished, inspired and committed to soaking up as much as I can from him. But the familiarity, trust and shared sense of humor that have developed between us is more the product of a working relationship between two artists than that of teacher and student. Our time together has been immensely productive, assisted by the talented and able Josh Rice, and has allowed us to lay the groundwork for our first collaborative production, Shank’s Mare (膝栗毛), which will make its world premiere in two short months at La MaMa Experimental Theatre as part of the 2015 LaMama Puppet Series. It has the honor of inaugurating LaMama’s new 6,500 square foot performance space, The Downstairs.

To begin, a short history of Koryu-sensei’s unique puppetry heritage: Near the end of the Edo period in Tokyo, the popularity of puppet companies using the three person puppet manipulation style (sanninzukkai), most recognizable today from the Bunraku theatre, began to wane. The problem was in many ways logistic. For a three character piece in the sanninzukkai style, nine puppeteers were required. It was at this point that the first Koryu Nishikawa introduced a technical and stylistic innovation that allowed a single puppeteer to do the job of three. Working within the traditional puppet structure, the company developed a rolling cart (rokuro kuruma) that allowed a puppeteer to sit and move about the stage, holding the puppet’s feet between his toes. The right hand of the puppeteer controlled the puppet’s right hand and the left hand controlled the head and left arm. The form became known as kuruma ningyo (cart puppetry) and was based in Hachioji, a city one hour’s drive from metropolitan Tokyo. The tradition of Hachioji Kuruma Ningyo has continued unbroken for 160 years and Koryu Nishikawa V is the 5th generation iemoto or master of the tradition.

By the time I met Koryu-san, he had pushed the boundaries of the traditional style even further, creating kuruma ningyo puppets of western characters, teaching abroad, and touring with his company to over 40 foreign countries. A strong bond developed between us based on Koryu-san’s openness and willing to share his tradition and my own fascination with the traditional Japanese puppetry forms that have been so influential in the West. Over the course of our many trips back and forth between Japan and the US, we developed the idea of creating a piece that might combine the traditional Japanese form with my own “American-style” kuruma ningyo puppets, throwing live feed video puppetry into the mix as well. In April of 2014, we created the first workshop version of Shank’s Mare at Sarah Lawrence College.

The title Shank’s Mare is inspired by a famous Japanese ningyo joruri play called Tokaido-chu Hizakurige about the misadventures of a pair of traveling merchants on the Tokaido road between Edo and Kyoto. ”Hiza” means knee and “kurige” refers to the deep lustrous brown color of well-bred and well-fed horses. “Hizakurige” means to travel by foot, to make a journey without using any conveyance other than one’s own feet; The term connotes traveling by means of one’s own physical strength , using one’s body like a well-bred horse. Our idea was to create a show which could bring our different artistic aesthetics together and allow us to cross cultural paths on stage. The convention of two characters on walking pilgrimages, one from the Japanese tradition and one from a Western tradition, took hold and has become the primary dramatic structure of the piece.

During our August residency at Hachioji Kuruma Ningyo we focused on developing the performance material that came out of our first workshop into a full fledged production. We both had ideas we wanted to continue to explore and discuss with each other in person. In addition, with the help of Koryu-san and some of my longtime friends in the Japanese puppetry community, we were able to interest and enlist the master wigmaker at the Bunraku National Theatre in Osaka in designing the hair for the American-made puppets used in the production. We also worked out the logistical details for the further rehearsal and development of Shank’s Mare, much of which will occur in the U.S. before Koryu-san arrives here in late October.

Our first day in Japan, our minds slightly fogged over by the haze of jet lag, began with a visit to Takao-san, a holy mountain near Koryu-san’s home that houses the Yakouin Yukiji Buddhist monastery and has a long association with kuruma ningyo. While true pilgrims climb stairs the entire way to the top, Koryu-san’s local fame allowed him to get us a free ride up the mountain by funicular; we crawled up the mountain at a 31-degree pitch. At the top, Koryu-san treated us to an incredible vegetarian meal within the monastery (one of many amazing culinary experiences in Japan), followed by a brief audience with the head monk of the cloister in his chambers. On our way back to Koryu-san’s theatre and studio, we made a stop at the sprawling Hachioji cemetery to visit the Buddhist grave of Koryu-san’s ancestors. The ashes of Koryu Nishikawa II, III, & IV are interred here. Sensei tidied up the area and had us pour water over the shrine in the tradition of tesui (purification by water). The practice of ancestor worship is something very close to my own experience growing up in Hawai’i, and Josh and I felt truly ready to work having paid our respects to our artistic forbearers.

Some of our residency time overlapped with a workshop Koryu-san was conducting with intermediate school students from the Hachioji area, offering us an opportunity to absorb and practice traditional kuruma ningyo. However, Josh and I were throughly put to shame by Koryu-sensei’s 13 year old students, who seemed completely fine rehearsing with the same heavy traditional Sanbaso puppets that left us writhing in pain. Sensei also called on Josh to assist him with the taiko (large drum) during percussion rehearsals with the students. Reconnecting with the traditional form and the process of repetition by which students learn the movements was an important part of our time in Hachioji. The traditional learning process can be very frustrating for someone coming from a Western theatre perspective because there is almost no emphasis on breaking down and analyzing individual movements. Instead, rehearsals of traditional works focus on repeating sequences and learning the musical rhythms within them. Knowing this traditional model makes Koryu-san’s willingness to enter into our own open-ended, devised style of creating a new work that much more remarkable. Experiencing for ourselves how difficult it is to bring true life to the traditional puppets and do so through apparently effortless mastery was an important reminder of the extraordinary strength and skill Koryu-san has achieved as a puppeteer.

Shank’s Mare weaves together two parallel stories, one performed by Koryu-san and one by our American company. Having rehearsed these sections separately, during our April 2014 workshop we interlaced them with great success. I felt Koryu-san’s puppet character (named Kandata) could be fleshed out even further and arrived in Japan hoping we could strengthen the dynamic of his character to represent his terrible fall in fortune and morality, from light to darkness. In addition, the piece is framed through the eyes of Shakyamuni Buddha, a god or kami, also played by Koryu-san, who observes the life paths of humans from on high. It seemed incongruous in our first workshop that Shakyamuni would appear in her true form directly to the human characters. I brought a sanninzukkai-style puppet of a stag with me to Japan to experiment with, hoping the appearance of this totemic animal might offer the appropriate level of separation between the divine and material world. The deer could approach the human characters in place of Shakyamuni Buddha. In Japan deer are believed to be messengers of the gods. It worked very well and two of Koryu-san’s younger students, Satomi Kishiyama and Yuto Yamaniwa, puppeteered with Josh to create a basic structure for the manipulation of this divine animal.

After reviewing the video of our 2014 workshop, Koryu-san and I agreed that the story of Kandata’s fall could have stronger parallels to the American storyline I had established of the Old Man and his disciple and their quest for enlightenment. In our discussions, Josh suggested Kandata’s own loss of a child or young disciple as the possible trigger for the character’s murderous rage against the world. It seemed we stumbled on an idea that made both dramaturgical sense and reinforced the connection between the two storylines. Further discussion followed and Koryu-san led us into the storage room of puppet heads at the theatre to look at possible character heads for Kandata and his child disciple. Being among the puppet heads of Samurai, fools, maidens and heroes was astonishing — another peek into the intricate and varied history of kuruma ningyo.

Late in the trip, we made another pilgrimage to the revered Bunraku National Theatre in Osaka, about 2 1/2 hours south of Tokyo by shinkansen (bullet train). As the landscape rocketed by, the contrast between the modernity of Japan’s massive public transportation system and our mission to research traditional puppetry practices for a show about an old fashioned walking journey was surprisingly satisfying. With Koryu-san as our guide, we made it to the theatre to meet several of the incredible artisans working behind the scenes to create the puppets used in performance by the Bunraku theatre. On my first long term trip to Japan, I had spent two weeks observing and sketching the urakata (backstage artisans) in their workshop at the theatre. Ten years later, after numerous trips, visits, and much correspondence, I have nurtured a friendship with two of the most important people there,Tanoshi Murao and Akiko Takahashi.

Tanoshi Murao, the ningyo-shi (puppet maker) is responsible for maintaining and repairing the puppet heads used in Bunraku. Using crushed seashell paste, glue from the bones of fish, and tiny pieces of whale baleen for springs, Murao-san works with ancient techniques to prepare the heads of every character used by the Bunraku puppeteers in performance. He is soft-spoken and gentle, showing us the inner workings of each head and special characters like a puppet of a nine-tailed fox, one of few animal puppets used in performance. Above Murao-san’s station hangs a portrait of Oe Minosuke, a master carver and his teacher, who, following the destruction of Osaka during World War II, embarked on a campaign to rebuild puppet heads and restore the Bunraku tradition.

Akiko Takahashi, the tokayama (wigmaker) is another traditional master. Her teacher is Nagoshi-sensei, formerly of the Bunraku National Theatre, who has spent a lifetime shaping the hairstyles that define the different characters and classes of the puppets. Akiko-san had to make great personal sacrifices to study under Nagoshi-sensei and is now the head wigmaker at the theatre. I was elated to see her. Akiko had agreed to create the hairstyles for our two American kuruma ningyo puppets, and I was nervous as a schoolboy as I removed the carved heads from their wrapping and showed them to her. For the next hour we talked about the heads, the character of the Old Man and the Girl, with Akiko pulling out different tufts of hair to press against their faces and showing examples of wig styles on traditional puppets. It was extraordinary to hear her describe how the cut of the hair could define the character of each head. During this process we debated whether to use human hair, dyed yak hair or brushed silk as the material for the wigs. Due to the nature of the carved gouges on the heads, Akiko proposed gluing the styled hairpiece directly to the heads. She will create separate eyebrow and beard pieces that I will glue and position myself once the heads are returned. In addition, she was very concerned about the maintenance of the hair and promised to give us full instructions about brushing, caring for and preserving the hairstyles. Occasionally, as we stood gathered around the heads like old friends, Murao-san and Koryu-san would offer a comment about the hairstyles and methods for fabricating and attaching the hairpieces. At one point, I glanced down to see the American-made heads on a table next to the traditional Japanese puppets and shivered with excitement.

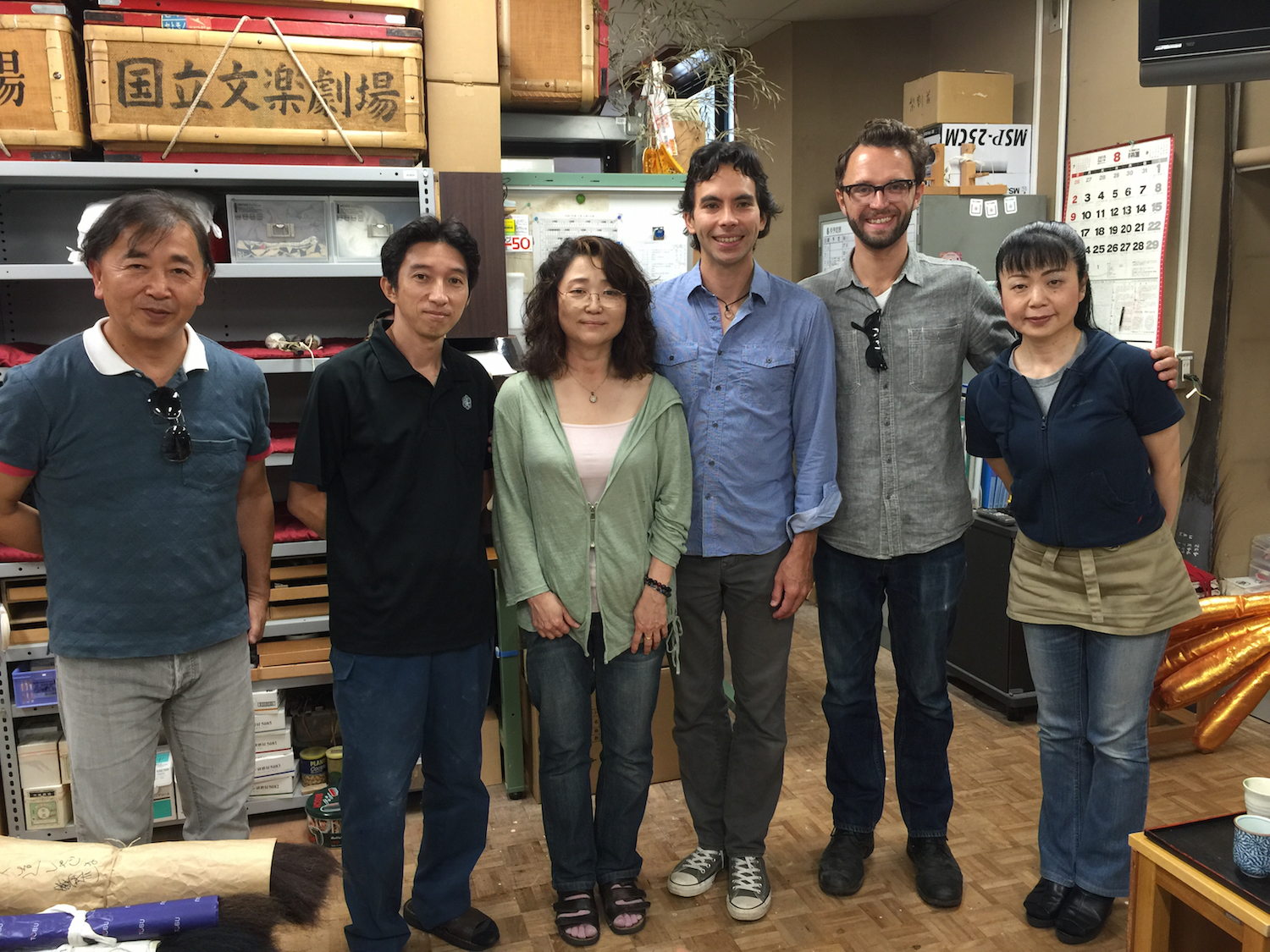

Shank’s Mare is meant to be a collaboration of Japanese and American puppetry styles, but through Akiko-san’s work on the hair of heads carved by Kevin White, the figures themselves become an international collaboration. As we were about to say goodbye, I was still overwhelmed that Akiko had agreed to work with us. Another happy coincidence was that Manami Sakamoto, practitioner of the otome bunraku (maiden Bunraku) style of puppetry, was also engaged as an assistant wigmaker in the backstage workshop. We took a photo together and Koryu-sensei led us back to the train station. On the way, he bumped into a middle aged man on his way to the theatre. They exchanged greetings and as we continued on he said, “One of the most famous shamisen players.”

Our final days were filled with further training and rehearsal combined with ongoing discussions, through our translator Kanako Hiyama ,working via Skype, about the logistics and budget of the New York premiere and a possible Japanese tour in the summer of 2016. One of the fantastic images that remains with me from our last days together is driving through the never-ending megalopolis of Tokyo with Koryu-san at the wheel, playing heavy metal on the radio. On the day that Josh was to leave, Koryu-san took us to an elementary school in the Akabane district of Tokyo where he was doing a short performance for school children. For Josh and I, it was an incredible event because we were able to watch Koryu-san rehearse with a live shamisen player and gidayu (chanter) in a tiny teacher’s lounge at the school. It is one of few times I have been able to see Koryu-san rehearsing a traditional piece with live music.

The plucked shamisen and vocal undulations of the gidayu reverberated in the tiny space of the lounge, while Koryu-san, his eyes closed, holding the puppet before him, channelled their sound. I was struck once again by the immense cultural and traditional knowledge he carries and his unique and challenging position in modern Japan. Early in our visit, I had sat down with Ryuji Nishikawa, Koryu-san’s brother, in the local izakaya (drinking house) a short walk from the Kuruma Ningyo theater. As the night wore on, Ryuji confessed that neither his son, nor Koryu-san’s son would continue the family tradition. He told me this with no trace of resentment, only a tinge of sadness. It left me wondering, who will be Koryu Nishikawa VI? There is no easy answer to this question. I was tempted to ask Koryu-san about it, but couldn’t bring myself to do it. In the end, perhaps what is important is not what may or may not be but what we can do together in the here and now. This trip has left me rejuvenated, energized about our work and in even greater awe of the man who has been my window into traditional Japanese puppetry.

Tom Lee

New York City, 22 September 2015